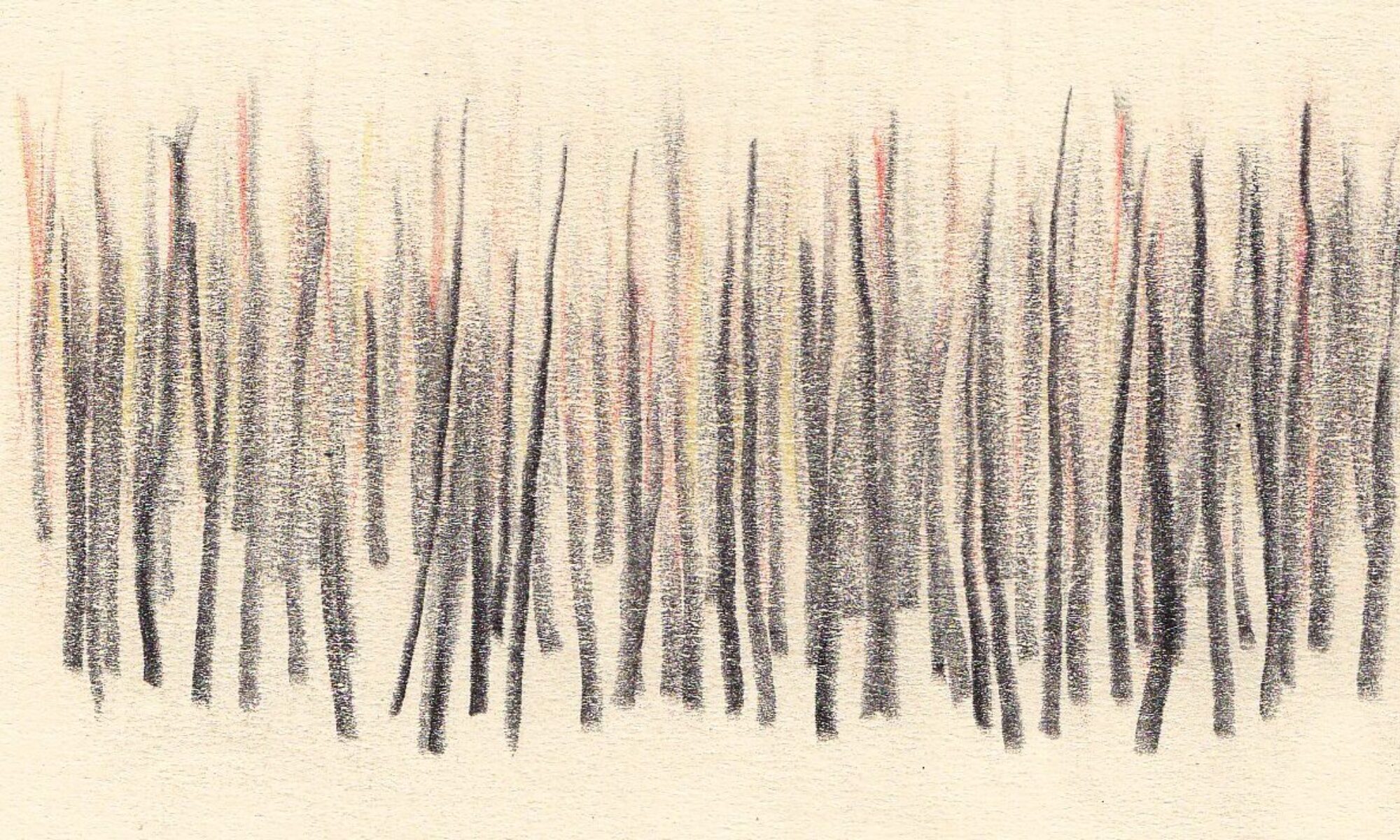

Irene is the city visible when you lean out from the edge of the plateau at the hour when the lights come on, and in the limpid air, the pink of the settlement can be discerned spread out in the distance below: where the windows are more concentrated, where it thins out in dimly lighted alleys, where it collects the shadows of gardens, where it raises towers with signal fires; and if the evening is misty, a hazy glow swells like a milky sponge at the foot of the gulleys.

Travelers on the plateau, shepherds shifting their flocks, bird-catchers watching their nets, hermits gathering greens: all look down and speak of Irene. At times the wind brings a music of bass drums and trumpets, the bang of firecrackers in the light-display of a festival; at times the rattle of guns, the explosion of a powder magazine in the sky yellow with the fires of civil war. Those who look down from the heights conjecture about what is happening in the city; they wonder if it would be pleasant or unpleasant to be in Irene that evening. Not that they have any intention of going there (in any case the roads winding down to the valley are bad), but Irene is a magnet for the eyes and thoughts of those who stay up above.

At this point Kublai Khan expects Marco to speak of Irene as it is seen from within. But Marco cannot do this: he has not succeeded in discovering which is the city that those of the plateau call Irene. For that matter, it is of slight importance: if you saw it, standing in its midst, it would be a different city; Irene is a name for a city in the distance, and if you approach, it changes.

For those who pass it without entering, the city is one thing; it is another for those who are trapped by it and never leave. There is the city where you arrive for the first time; and there is another city which you leave never to return. Each deserves a different name; perhaps I have already spoken of Irene under other names; perhaps I have spoken only of Irene.