Like Laudomia, every city has at its side another city whose inhabitants are called by the same names: it is the Laudomia of the dead, the cemetery. But Laudomia’s special faculty is that of being not only double, but triple; it comprehends, in short, a third Laudomia, the city of the unborn.

The properties of the double city are well known. The more the Laudomia of the living becomes crowded and expanded, the more the expanse of tombs increases beyond the walls. The streets of the Laudomia of the dead are just wide enough to allow the gravedigger’s cart to pass, and many windowless buildings look out on them; but the pattern of the streets and the arrangement of the dwellings repeat those of the living Laudomia, and in both, families are more and more crowded together, in compartments crammed one above the other. On fine afternoons the living population pays a visit to the dead and they decipher their own names on their stone slabs: like the city of the living, this other city communicates a history of toil, anger, illusions, emotions; only here all has become necessary, divorced from chance, categorized, set in order. And to feel sure of itself, the living Laudomia has to seek in the Laudomia of the dead the explanation of itself, even at the risk of finding more there, or less: explanations for more than one Laudomia, for different cities that could have been and were not, or reasons that are incomplete, contradictory, disappointing.

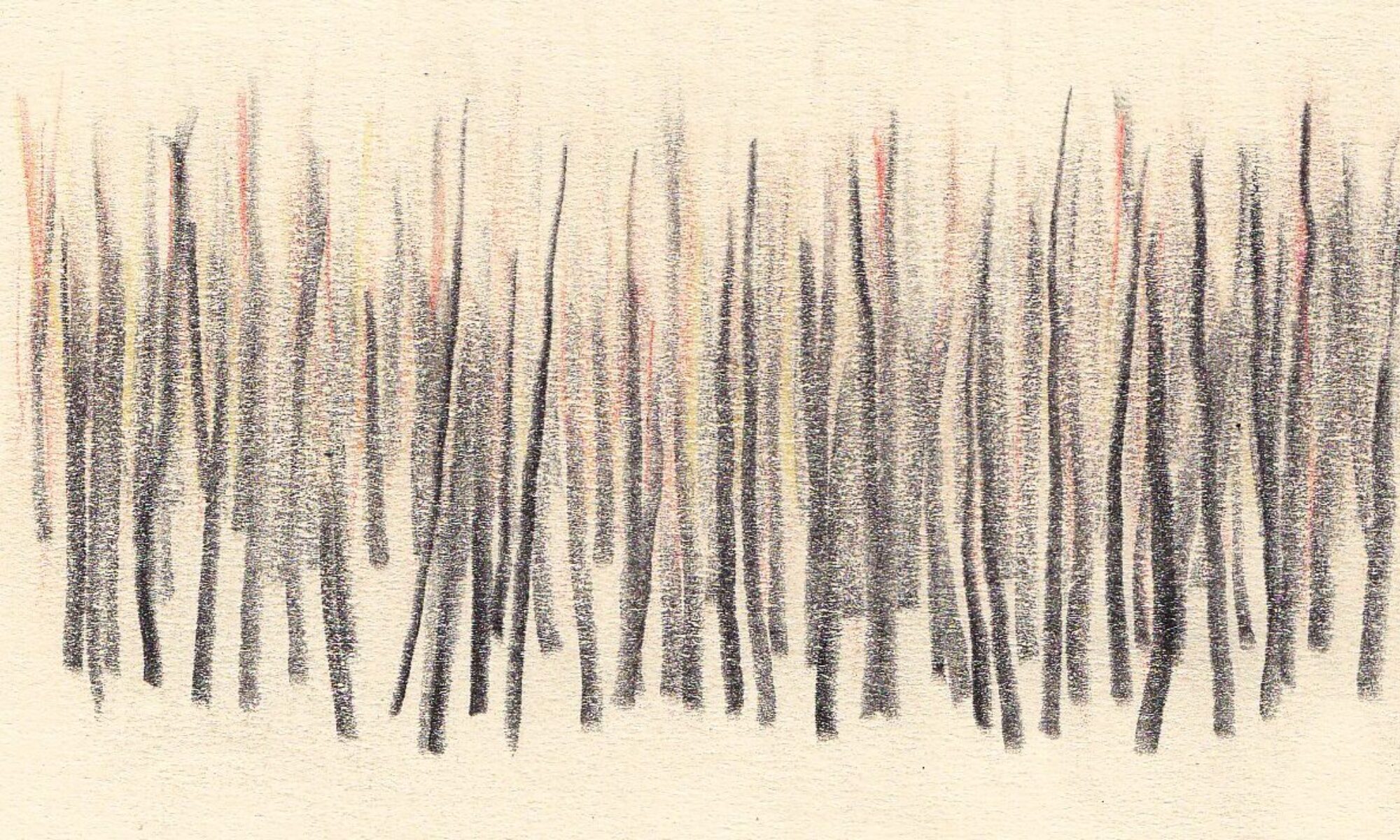

Rightly, Laudomia assigns an equally vast residence to those who are still to be born. Naturally the space is not in proportion to their number, which is presumably infinite, but since the area is empty, surrounded by an architecture all niches and bays and grooves, and since the unborn can be imagined of any size, big as mice or silkworms or ants or ants’ eggs, there is nothing against imaging them erect or crouching on every object or bracket that juts from the walls, on every capital or plinth, lined up or dispersed, intent on the concerns of their future life, and so you can contemplate in a marble vein all Laudomia of a hundred or a thousand years hence, crowded with multitudes in clothing never seen before, all in eggplant-colored barracans, for example, or with turkey feathers on their turbans, and you can recognize your own descendants and those of other families, friendly or hostile, of debtors and creditors, continuing their affairs, revenges, marrying for love or for money. The living of Laudomia frequent the house of the unborn to interrogate them: footsteps echo beneath the hollow domes; the questions are asked in silence; and it is always about themselves that the living ask, not about those who are to come. One man is concerned with leaving behind him an illustrious reputation, another wants his shame to be forgotten; all would like to follow the thread of their own actions’ consequences; but the more they sharpen their eyes, the less they can discern a continuous line; the future inhabitants of Laudomia seem like dots, grains of dust, detached from any before or after.

The Laudomia of the unborn does not transmit, like the city of the dead, any sense of security to the inhabitants of the living Laudomia: only alarm. In the end, the visitors’ thoughts find two paths open before them, and there is no telling which harbors more anguish: either you must think that the number of the unborn is far greater than the total of all the living and all the dead, and then in every pore of the stone there are invisible hordes, jammed on the funnel-sides as in the stands of a stadium, and since with each generation Laudomia’s descendants are multiplied, every funnel contains hundreds of other funnels each with millions of persons who are to be born, thrusting their necks out and opening their mouths to escape suffocation. Or else you think that Laudomia, too, will disappear, no telling when, and all its citizens with it; in other words the generations will follow one another until they reach a certain number and will then go no further. Then the Laudomia of the dead and that of the unborn are like the two bulbs of an hourglass which is not turned over; each passage between birth and death is a grain of sand that passes the neck, and there will be a last inhabitant of Laudomia born, a last grain to fall, which is now at the top of the pile, waiting.