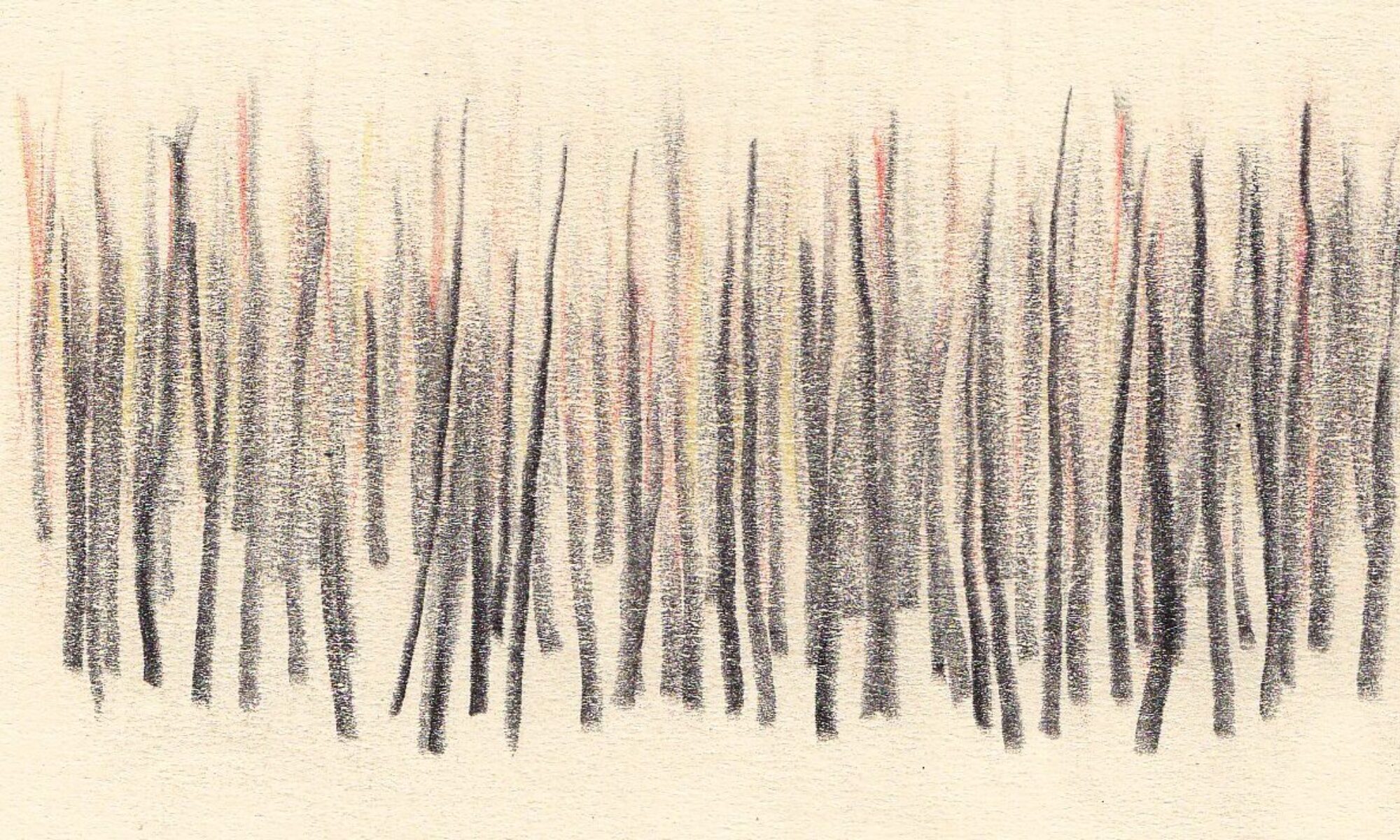

To tell you about Penthesilea I should begin by describing the entrance to the city. You, no doubt, imagine seeing a girdle of walls rising from the dusty plain as you slowly approach the gate, guarded by customs men who are already casting oblique glances at your bundles. Until you have reached it you are outside it; you pass beneath an archway and you find yourself within the city its compact thickness surrounds you; carved in its stone there is a pattern that will be revealed to you if you follow its jagged outline.

If this is what you believe, you are wrong: Penthesilea is different. You

advance for hours and it is not clear to you whether you are already in the

city’s midst or still outside it. Like a lake with low shores lost in swamps,

so Penthesilea spreads for miles around, a soupy city diluted in the plain;

pale buildings back to back in mangy fields, among plank fences and corrugated

iron sheds. Every now and then at the edges of the street a cluster of

constructions with shallow facades, very tall or very low, like a snaggle-toothed

comb, seems to indicate that from there the city’s texture will thicken. But

you continue and you find instead other vague spaces, then a rusty suburb of

workshops and warehouses, a cemetery, a carnival with Ferris wheel, a shambles.

You start down a street of scrawny shops which fades amid patches of leprous

countryside.

If you ask the people you meet, “Where is Penthesilea?” they make a broad gesture which may mean “Here” or else “Farther on”, or “All around you,” or even “In the opposite direction.”

“I mean the city,” you ask, insistently.

“We come here every morning to work,” someone answers, while others

say, “We come back here at night to sleep.”

“But the city where people live?” you ask.

“It must be that way,” they say, and some raise their arms obliquely

toward an aggregation of opaque polyhedrons on the horizon, while others

indicate, behind you, the specter of other spires.

“Then I’ve gone past it without realizing it?”

“No, try going straight ahead.”

And so you continue, passing from outskirts to outskirts, and the time comes to

leave Penthesilea. You ask for the road out of the city; you pass again the

string of scattered suburbs like a freckled pigmentation; night falls; windows

come alight, here more concentrated, sparser there.

You have given up trying to understand whether, hidden in some sac or wrinkle

of these dilapidated surroundings there exists a Penthesilea the visitor can

recognize and remember, or whether Penthesilea is only the outskirts itself.

The question that now begins to gnaw at your mind is more anguished: outside

Penthesilea does an outside exist? Or, no matter how far you go from the city,

will you only pass from one limbo to another, never managing to leave it?